“One day when he was alone, the tempter appeared. A little black bird…set about fluttering around him, approaching his face in an annoying manner, so close that the holy man could have caught it in his hand if he had wanted to. He made the sign of the Cross, and the bird went away. But then, when the bird had gone, a carnal temptation came upon him so strongly that this holy man had never before felt anything like it. Some time before this, he had seen a woman that the evil spirit brought before the eyes of his soul. Such a fire was enkindled in the spirit of God’s servant at the memory of this beauty that he could no longer contain the flame of love in his heart. He was on the point of deciding to quit the desert, overcome by sensuality.”*

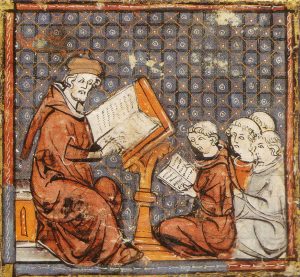

The famous pope, Gregory the Great, wrote this biography of Benedict of Nursia in the late sixth century. These two men played significant roles in the development of the two most important medieval institutions: the papacy and monasticism. Gregory set the ideal pattern for the medieval pope through his writings and actions. He lived most of his adult life as a monk himself. He wrote this Life of St Benedict as part of a larger work of dialogues on the Italian hermits and monastic saints. In this chapter Gregory described how St. Benedict dealt with sinful lusts of the flesh. Gregory continued:

“Suddenly, touched by grace from on high, he came back to himself and, noticing close at hand some thick bushes of nettles and brambles, he took off his clothes and threw himself naked among the thorns and fierce nettles. These flesh wounds served as a bodily outlet for the wound in his soul, pleasure being changed into pain. By this exterior burning, which was a beneficial chastisement, he extinguished the interior fire which was harmful. He vanquished sin by changing one fire into another.”**

In the next section, Gregory explained that Benedict told his disciples that he never felt sexual temptation again. This event inspired many others to join Benedict in the Italian countryside. He had proven himself and overcome temptation. “Freed from the temptation to vice,” Gregory wrote, “he could rightly become a master of evil.”***

Benedict was a real man who died in 547 around the time Gregory was born. He wrote the most influential guidebook for the monastic life titled merely, The Rule. Gregory intended these narratives to inspire imitation in faith and action by his Christian readers. This tale of Benedict’s triumph over sexual lust inspired a basic principle of medieval monasticism: when it takes place for the right reasons, bodily pain leads to the sanctification of the soul. Exterior discipline can change one inwardly and assist in overcoming sin.

*Gregory the Great, The Life of Saint Benedict II, trans. Hilary Costello and Eoin de Bhaldraithe (Petersham, MA: Saint Bede’s, 1993), p. 21

**Ibid. [Emphasis added]

***Ibid.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Annunciation of the Lord

Leonardo da Vinci’s Annunciation of the Lord