On October 28, 2023, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu began his speech to announce the invasion of Gaza in response to an attack by Hamas with a reference to the enemy of the ancient Israelites: Amalek. He referred specifically to King Saul’s attack on the Amalekites. Some have interpreted his rhetoric as a call for the utter destruction of a group of people. Others have argued that this appeal only focused on Hamas as a terrorist group and not the entire Arab population of Gaza. However, Netanyahu’s reference to Amalek reminded me of the theological rhetoric related to the preaching of the First Crusade.*

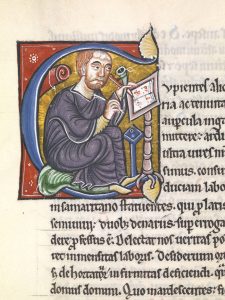

Pope Urban II preached a sermon at the council of Clermont on November 27, 1095. This event led to a massive armed pilgrimage known as the First Crusade. According to Baldric of Bourgueil (a monastic chronicler and eyewitness of the sermon), Urban concluded his sermon with a reference to Amalek as a forerunner to the Turks and other Muslims in the Middle East in the late 11th century:

“And he turned to the bishops: ‘You,’ he said, ‘you brothers and fellow bishops, you fellow priests and co-heirs of Christ, announce this very thing throughout the churches entrusted to you, and preach the way to Jerusalem powerfully and with complete eloquence. Secure in Christ, agree a swift pardon to those who have confessed their sins committed through ignorance. Moreover, you who are going to make the journey, you will have us praying for you; let us have you fighting for the people of God. It is our part to pray; let yours be to fight against the Amalachites [sic]. With Moses we shall stretch out unwearied hands to heaven in prayer; as fearless warriors you are stretching forth and brandishing the sword against Amalech [sic].’ “**

In the quote above, Baldric has Urban refer to Exodus 17:8-14 . This text records a battle when Joshua led Israelites against the Amalekites while Moses stood with his hands raised on the hill overlooking the area. Here Urban and bishops are to play the role of Moses as they pray for the success of the First Crusaders against the Muslims, that is, the new Amalekites. The chroniclers of the First Crusade interpreted the armed pilgrims as the new Israelites going into the Promised Land in fulfillment of Old Testament events. In so doing, they borrowed from their (mostly) monastic theology that followed the earlier patristic allegorical tradition of interpreting the Old Testament. The early twelfth-century theologian, Honorius Augustodunensis, compared the procession at the beginning of the Mass to the ancient Israelites carrying the holiest of objects into battle:

“The priests carried the ark of the covenant, and Aaron the high priest follows in his vestments, and Moses, the leader of the people, with his rod. On their way, Amalek met the with his army and tried to block their way. But Joshua came out victorious and opened the way for the people toward their fatherland.”***

In this section, Honorius explained how the Church’s processional march during the liturgy spiritually fulfilled the ancient battles led by Moses and Joshua against the Pharaoh, Amalek, and the Canaanites at Jericho. The reference to Amalek seemed like a common exegetical trope around 1100 that also appeared in sermons. For example, Ivo of Chartres, bishop of Chartres from 1090 to 1115 identified Moses’ lifting up of his hands in prayer as the sign of the cross by which Jesus conquered Amalek.****

These references to the fulfillment of the Old Testament victory over Amalek as a pre-figuration of Christ’s victory on the cross and to the Crusaders’ victories became a standard part of the exegetical tradition related to the First Crusade. They also appear in liturgies prayed and sung to intercede to God for later Crusades’ success. I highly recommend two excellent books that show how Christian theologians and devotional writers did this:

M. Cecilia Gaposchkin, Invisible Weapons: Liturgy and the Making of the Crusade Ideology (Ithaca 2017).

Katherine Allen Smith, The Bible and Crusade Narrative in the Twelfth Century (Woodbridge 2020).

*“You must remember what Amalek has done to you, says our Holy Bible: ‘Now go and attack Amalek, and utterly destroy all that they have, and do not spare them. But kill both man and woman, infant and nursing child, ox and sheep, camel and donkey.’ And we do remember. And we are fighting.” Netanyahu’s Speech in which he quotes: I Samuel 15:1-10

**Baldric of Bourgueil, History of the Jerusalemites, trans. Susan B Edington (Woodbridge, 2020), p. 49.

***Honorius Augustodunensis, Jewel of the Soul, vol. 1, chap. 68, trans. Zachary Thomas and Gerhard Eger (London, 2023), p. 131.

****Ivo of Chartres, Sermo V, Patrologia Latina 162: 541A.