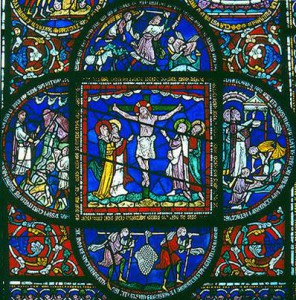

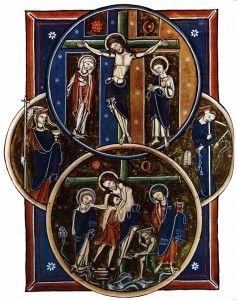

“Who can contemplate Eternity being born, Power itself failing, Bread going hungry, the Spring itself growing thirsty, without becoming speechless? But who can contemplate the beginning of our salvation, the day of human healing, without bursting forth in a voice of exultation and praise, the sound of one keeping festival?* God has been made a man; who knows how to speak about that? Our Jesus, our Savior, our joy, comes among us; who can keep silent? Therefore, let us rejoice in God, our salvation.* If the angels see God’s face* in jubilation, we ought at least to see God’s back* not without jubilation? ” Aelred of Rievaulx, ‘Sermon 30: For the Nativity of the Lord’ in Aelred of Rievaulx: The Liturgical Sermons, The Second Clairvaux Collection, trans. Marie Anne Mayeski (Collegeville, MN 2016), pp. 3-4 [Italics in original, but Bold print added]

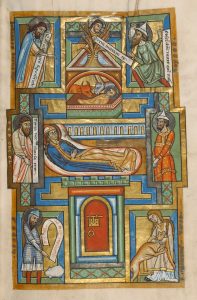

Aelred of Rievaulx exemplifies the twelfth-century Cistercians’ emphasis on the Incarnation and passion of Christ in this Christmas sermon. How could God become a human being? Why did he do so? Aelred hints at this when he states that believers should see God’s back in jubilation. Cistercian theologians understood Moses’ seeing God’s back as a type of the incarnate Christ. Aelred then describes how Moses encountering God in the burning bush foreshadowed the Word becoming flesh. As a bush contained thorns so Christ in flesh bore the thorns of sin in his body:

“Will I now dare to say that that flesh in which was the Word that is God, God who is the consuming fire–dare I say that that flesh was the bush? Without a doubt, it is the bush, a bush that had thorns that were not his own but our thorns. Because it was our infirmities that he bore, our sufferings that he endured; he was wounded for our offenses and worn out for our sins.* Let us remember his passion, let us see in what manner Pilate crowned him with thorns and said, Behold the man.* True man, true flesh, true bush, carrying our thorns. But why on the head? O Lord my God, it is not enough that you may be seen to bear my thorns unless you also bear them on your head! Lord my God, crowned with my thorns!” Ibid. 5.

*Psalm 41:3

*Psalm 94:1

*Matthew 18:20

*Exodus 33:23

*Isaiah 53:4-5

*John 19:5