“The process of execution was also a sad and heartrending spectacle. In the middle of Place de la Revolution was erected a guillotine, in front of a colossal statue of Liberty, represented seated on a rock, a cap on her head, a spear in her hand, the other reposing on a shields. On the side the scaffold were drawn out a sufficient number of carts, with large baskets painted red, to receive heads and bodies of the victims. Those bearing the condemned moved on slowly to the foot of the guillotine; the culprits were led out in turn, and if necessary, supported by two of the executioner’s assistants, but their assistance was rarely required. Most of these unfortunates ascended the scaffold with a determined step–many of them looked up firmly on the menacing instrument of death, beholding for the last time the rays of the glorious sun, beaming on the polished axe: and I have seen some young men actually dance a few steps before they went up to be strapped to the perpendicular plane, which was then tilted to a horizontal plane in a moment, and ran on the grooves until the neck was secured and closed in by a moving board, when the head passed through what was called, in derision, ‘the republican toilet seat‘; the weighty knife was then dropped with a heavy fall; and, with incredible dexterity and rapidity, two executioners tossed the body into a basket, while another threw the head after it.”*

This is an eyewitness account of the executions in Paris during the French Revolution. In 1789 the upper middle class began a revolution that initially led to a Constitutional Monarchy and the end of early modern feudalism and aristocratic privileges in France. In August 1789 the self-proclaimed National Assembly wrote the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. This document included the basic concepts of freedom of speech and association, rights to private property, representative government, and the right to a fair trial. Over the next few years a process of radicalization took place for a number of reasons: War with other European powers, resistance from within France, and the complete collapse of any royal authority.

The Civil Constitution of the Clergy (July 1790), condemned by the pope, gave the new French government authority over the Catholic Church and led to civil war within France between the revolutionaries and traditional Catholic peasants. By 1793 France had become a Republic and its new leaders had executed the king. This new government promoted an official “de-christianization” policy of French society that included a new calendar, destroying religious art, vandalizing church property, and the arrest and sometimes execution of many priests, monks, and nuns.

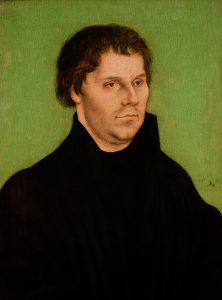

Maximilien Robespierre

In 1794, turning the tide of war in their favor against the First Coalition, the republican government sought to first ensure its own survival and then to possibly expand French territory. To accomplish this, the government had created the Committee of Public Safety in 1793 and it gradually became a the most powerful nine-person committee in France. They ordered a brutal repression of traditionalist resisters and eventually turned on one another. Maximilien Robespierre emerged as the most significant leader who ordered the execution of many fellow revolutionaries. He justified his ideas in February 1794 with the publication of Report on the Principles of Political Morality in which he wrote:

“If the spring of popular government in time of peace is virtue, the springs of popular government in revolution are at once virtue and terror: virtue, without which terror is fatal; terror, without which virtue is powerless. Terror is nothing other than justice, prompt, severe, inflexible; it is therefore an emanation of virtue; it is not so much a special principle as it is a consequence of the general principle of democracy applied to our country’s most urgent needs.”**

*J. G. Milligen, The Revolutionary Tribunal (Paris, October 1793) [Bold print added]

**Robespierre’s Report