“And whosoever shall exalt himself shall be humbled: and he that shall humble himself shall be exalted.” Matthew 23:12 (Douay-Rheims)

In my last post we saw how Augustine asserted that pride began as a perverse exaltation of the self above all else. This vice characterized the sinful community of human beings (city of Man) Pride Goes Before Destruction. Augustine pointed toward humility (given by the grace of God) as the foundation of virtue. This idea became the basis of medieval religious belief and practice. As pride actually abased those who exalt themselves through sin, humility exalts those who abase themselves through true humility. Augustine explained:

“Thus, in a surprising way, there is something in humility to exalt the mind, and something in exaltation to abase it. It certainly appears somewhat paradoxical that exaltation abases and humility exalts. But devout humility makes the mind subject to what is superior. Nothing is superior to God; and that is why humility exalts the mind by making it subject to God.” [Augustine, City of God 14. 13. trans. Henry Bettenson (London 1984), 572]

For this reason Augustine states that humility marks those who belong to the City of God and Christ, the ruler of that City. In order to remedy the human sin of pride, Augustine explains that God abased himself through mercy and demonstrated grace through taking on human nature. [Augustine, On the Merits and Forgiveness of Sins 26. 17.]

Medieval monastic theologians focused on humility as the foundation of faith and virtue. In his Rule, St Benedict depicted the monastic life as a ladder of humility with twelve steps: “Now the ladder erected is our life on earth, and if we humble our hearts the Lord will raise it to heaven.” The monastic life revolved around self-abasement of body and soul in absolute obedience to another’s will. [Rule of St Benedict chap. 7.]

As we saw in the previous post on pride, Bernard of Clairvaux (d.1153) adopted Benedict’s ladder imagery to examine the vices of pride and the virtues of humility. In opposition to pride, he defined humility as the virtue of having a low opinion of one’s self based on self-knowledge and the contempt of one’s own excellence. [Bernard, The Steps of Humility and Pride 1. 2; 4. 14, trans. M. Ambrose Conway OCSO. Kalamazoo 1989, 30, 42]

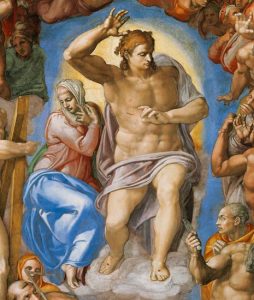

Munich, BSB Clm 14519, 5r

Genuine humility rests in the truth, results in mercy, and it leads to love (caritas). All of these virtues come from the incarnate Christ through faith and are practiced by monks through imitation. This is the manner by which monks (or Christians) may fulfill the commandment to love their neighbors as themselves. As Bernard wrote:

“You will never have real mercy for the failings of another until you know and realize that you have the same failings in your soul. Our Savior has given us the example. He willed to suffer so that he might know compassion; to learn mercy he shared our misery.” [Steps 3. 6, p. 35]

The depiction to the right reads: “the pride of the devil is conquered by the humility of the cross of Christ.” If you would like to see the original go here: BSB Clm 14159