“I consider in my mind these admirable gifts of God, namely the study of literature and of the humanities—and apart from the Gospel of Christ this world holds nothing more splendid nor more divine and I also consider, on the other hand, by what blindness the minds of men are enveloped in unnatural and Cimmerian* darkness; they spurn these true and greatest gifts, and with great effort they pursue means for their wishes and desires that are not only inferior but also ruinous and destructive to themselves. When I weigh these things in my heart, I am violently moved, for it comes to my mind by what dense darkness and, so to speak, black night the hearts of men are surrounded. I am not further astonished, if men are blind in things that are divine and beyond human understanding, when I see them thus treading under foot these their own and personal goods for which they are intended by divine providence, and which they could have comprehended and cherished.” Philip Melanchthon, “Preface to Homer,” in in The Great Tradition: Classic Readings on What It Means to Be An Educated Human Being, ed. Richard M. Gamble. Wilmington 2007, pp. 420-21.

*Cimmerian refers to a mythical place of darkness in Homer’s Odyssey.

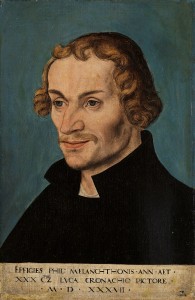

Philip Melanchthon delivered this oration around 1538 as he began to teach Homer’s famous works (the Illiad and the Odyssey). While he was a significant theologian, as a Renaissance humanist Melanchthon inspired the study of ancient Greek and the Latin classics through his curricular reforms at Wittenberg. He also promoted similar reforms at other German universities in the sixteenth century. In this work he explained the significance of the study of Homer and the classics. In brilliant rhetorical style Melanchthon lamented those who rejected these significant texts:

“We disdain….the study of the classics, by which the part of us that alone deserves the name ‘man,’ that is made in the image of God and for the possession of true and everlasting happiness, was meant to be refined and roused. Instead of these, we pursue with mad and blind effort I know not what illusions held out by Satan, and worthless shadows, and hitherto have not had the reverence to look at the sun.” Ibid., p. 421.

Melanchthon understood great literature as that which refines and rouses the image of God in human beings. He exhorted his hearers to turn away from demonic illusions and shadows and look toward the sun of true knowledge and understanding. However, most people seek to learn for economic advantage and even seek to suppress true learning.

“Each one rushes towards the mean and gainful arts, they are slaves to their detestable desires and to their stomachs, and they know no god besides these. Only very few take care to refine and honour [sic] their minds, the better and more the divine part of them. Just as in a noisy and drunken banquet men talk nonsense, laugh, bawl and make loud noise while some famous musician is playing, and they neither pay attention nor receive in their ears and hearts the sweetness of the music, nor enjoy it thoroughly, so at times, as if intoxicated and frantic with their desires, neither listen to the voices of the Muses nor pay attention to them. Those who by their authority and efforts should have eminently fostered and honoured [sic] these studies, the majority being barbarians and without education, greatly desire rather to see them oppressed and annihilated.” Ibid.