In the late eleventh century, a famous theologian wrote a book called: Cur deus homo (usually translated as Why God Became a Man). Born in Aosta in modern northern Italy in 1033, Anselm left his home in the late 1050s and settled in Normandy at the monastery of Bec in 1059. This meant that Duke William II of Normandy (King William I of England from 1066-86) became Anselm’s noble benefactor. Anselm served as prior and then abbot of Bec for many years before becoming archbishop of Canterbury in 1093. He spent much of his archbishopric in exile since both King William Rufus II (d.1100) and King Henry I (d.1135) were often at odds with archbishop’s reform program.*

Anselm wrote a number of works of great significance for philosophy, theology, and devotional practice. However, his most well-known work among modern scholars and theology students is Cur deus homo. Following the Platonic tradition, Anselm wrote this work as a dialogue between a teacher (Anselm) and his student (a fellow monk named Boso). Anselm wrote this book to answer the objections of unbelievers (mostly Jews) to the incarnation and death of Christ. However, the theological schools connected to cathedrals in northern France also engendered debate regarding the purpose of the incarnation. In the early part of the dialogue, Boso described the Jewish objections in the following manner:

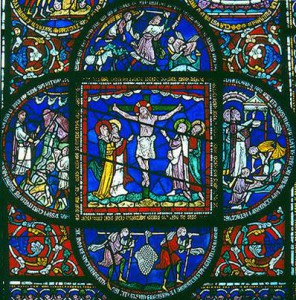

“The unbelievers…charge that we do God injury and insult when we assert that he descended into the womb of a woman, that he was born of a woman, that he grew, nourished by milk and human foods, and–not to speak of many other things that seem inappropriate for God–that he bore weariness, hunger, thirst, blows, and a cross and death between the thieves.”**

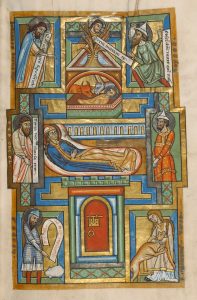

To the Jews it seemed irrational and certainly against the nature of God to do such things. Therefore, Anselm wanted to explain why it was fitting, rational, and right for God to become a human being. Most significantly, the incarnation became the means of God’s reconciliation with sinful humanity. In the Fall, human beings violated God’s honor through disobedience and suffered the just penalty of God’s anger. Justice demanded satisfaction of this debt, but God is merciful. This reconciliation could only take place if a man made satisfaction for the disobedience. However, only God could make such an offering because the offering must be greater than everything except God. Therefore, a God-man must necessarily perform it to redeem humanity as Anselm explained to Boso:

If then, as is certain, that the celestial city must be completed from among men, and this cannot happen unless the aforesaid satisfaction is made, while no one save God can make it and no one save man ought to make it, it is necessary for a God-Man to make it.***

*On Anselm see R.W. Southern, Saint Anselm: A Portrait in a Landscape (Cambridge 1990).

**Anselm of Canterbury, Why God Became Man i. iii., in A Scholastic Miscellany: Anselm to Ockham (Philadelphia 1956), p. 104.

***Anselm, Why God Became Man ii. vii., Scholastic Miscellany, p. 151; Cf. Southern, Saint Anselm, pp. 205-207.