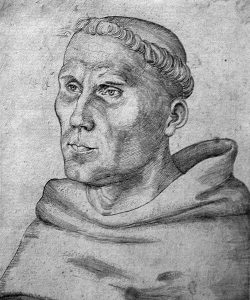

A close reading of Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses demonstrates that he was calling into question not only the doctrine of indulgences but also the late medieval sacrament of penance. Luther focused on the interior nature of repentance instead of sacramental penance administered by a priest. For instance, he wrote that truly repentant Christians already have complete remission of the penalty and guilt of sin without written indulgences (Thesis 36). Christians should not even seek to lessen the true penalty of sin through obtaining indulgences, but rather embrace the tribulation and the cross that characterized the outward form of true, inward repentance until death (Theses 3, 4, 40, 94, 95). Luther was asking a basic theological question: why would a truly repentant sinner want to receive an indulgence in place of fully participating in Christ’s passion through inner and outward repentance?*

In writing these things, Luther’s emphasis on interior repentance as the foundation of the outward act was similar to twelfth-century theologians’ focus on contrition as the inward part of penance and therefore, more significant. A great proponent of this emphasis on contrition and inner conversion, Peter Abelard (d.1142) criticized greedy bishops for granting partial indulgences at the dedication of churches and altars. These theologians questioned how giving a few coins as alms could remit or replace the outward acts of penance that resulted from a truly penitent soul. These criticisms led scholastic theologians in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries to significantly refine the doctrine of indulgences in relation to the sacrament of penance.**

These theological developments related to the doctrine of penance and indulgences emerged at the same time as a very significant religious and social movement in Western Europe known as the Crusades. While early forms of indulgences existed before the First Crusade, this movement stimulated the papacy’s expansion of the use of indulgences and the theological refinement of the doctrine of penance in the twelfth century. Pope Urban II’s plenary indulgence for the First Crusade reflected an earlier tradition of penitential practice. In the eleventh century after someone confessed a sin, a confessor imposed a penance, such as, fasting or a pilgrimage depending on the severity of the sinful action. Then, only after the sinner had fulfilled his or her penance, the confessor gave absolution.***

Based on the average layman’s inability to fully satisfy the debt of his sin through acts of penance, the Church offered the commutation of penance. This meant that the penitent could commute or exchange the completion of his or her sin through a lesser act that benefited the Church or others, such as, giving a donation to a monastery or specific church. Urban II’s indulgence went beyond a mere commutation and rather offered an armed pilgrimage to reconquer Jerusalem and pray at the Holy Sepulcher as a super-satisfactory act that completed all penance owed for all confessed sins. The burden of penances weighed heavily on a Christian knight’s soul and Urban offered an incredible opportunity to lift it.****

During the twelfth century the understanding of indulgences shifted to reflect a new theology of penance that emphasized contrition for sin and confession to a priest followed by absolution. Having received the forgiveness of sin’s guilt, the penitent then performed acts of satisfaction to pay for the penalty of sin. The notion of purgatory as a place where a sinner fulfilled his or her satisfaction through suffering became more precisely defined. An indulgence granted by the proper ecclesiastical authority (i.e., the pope) remitted the debt of the temporal punishment of sin. The papacy’s plenary indulgences remained limited to participants in various crusades, but bishops also expanded their offering of partial indulgences for confessed sins in the twelfth century. While some indulgences required attendance at churches or the veneration of relics, others allowed the penitent to give alms, donations for the building of churches, monasteries, hospitals, or even bridges without a specific requirement of attendance. During this century all indulgences began to emphasize the connection with contrition and oral confession. Instead of discouraging the practice of confession among laity, it seemed to increase lay participation in religious life or at least the bishops hoped it would do so. Additionally, indulgence promoters (questors) operated in the twelfth century and some unscrupulously absconded with the money raised through donations.*****

In the early thirteenth century the use of the indulgences expanded to include those who not only participated in a crusade, but also those who supported a crusade through prayer or financial support. Innocent III (1198-1216), who had been trained by scholastic theologians in Paris, sought to include all of Christian society in the crusading movement by arranging liturgical processions and appointing specific times for crusade preaching. Those who participated in these events could at the very least receive partial indulgences for contritely confessed sins. He also appointed preachers who promoted the more refined view of the sacrament of penance and combined crusade preaching with social and moral reform. At this same time Innocent approved the practice of indiscriminately allowing people to take the cross. Then, those who could not fulfill their crusader vow could later redeem or commute them and receive the plenary indulgence. This practice of vow redemption led to many individuals supporting the cause of crusading through financial support and prayer in thirteenth century.******

Late medieval popes expanded the availability of plenary indulgences to all penitents in the fourteenth century. Boniface VIII introduced the jubilee indulgence associated with a pilgrimage to Rome in 1300. Additionally, the bishops and popes continued to offer indulgences for deathbed confessions and other religious acts of devotion. By the fifteenth century the complete doctrine and practice of indulgences, which Martin Luther later attacked in 1517, had become commonplace. As the successors of St Peter, the Roman popes claimed that they held the power to a heavenly treasury filled with the merit earned by Christ’s Passion. Lastly, in the late fifteenth century, Pope Sixtus IV proclaimed that souls in purgatory could benefit from the papal granting of indulgences from that treasury of merit. Thereby, he only affirmed a practice that had existed for some time.*******

*Ninety-Five Theses see Luther’s Works, vol. 31 (Philadelphia 1957), 25-33.

**Matthew Phillips, “The Thief’s Cross: Crusade and Penance in Alan of Lille’s Sermo de cruce domini,” Crusades 5 (2006): 151-53; Nicholas Vincent, ‘Some Pardoners’ Tales: The Earliest English Indulgences’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 12 (2002), 23-58.

***Martin Luther referred to this practice in Thesis 12 which reads, “In former times canonical penalties were imposed, not after, but before absolution, as tests of true contrition.”

****Ibid, 28-29; Marcus Bull, Knightly Piety and the Lay Response to the First Crusade (Oxford 1993), 166-71. For a general overview of the relationship between the Crusades and indulgences see Jessalynn Bird, “Indulgences and Penance,” ed. Alan V. Murray, The Crusades: An Encyclopedia, vol. 2 (Oxford 2006), 633-37.

*****Vincent, “Some Pardoners’ Tales,” 38-50; Mary C. Mansfield, The Humiliation of Sinners (Ithaca 1995), 34-35.

******Jessalynn Bird, “Innocent III, Peter the Chanter’s Circle, and the Crusade Indulgence: Theory, Implementation, and Aftermath,” in Innocenzo III: Urbs et Orbis, Atti del Congresso Internazionale (Rome, 9-15 September 1998), ed. Andrea Sommerlechner (2003), 501-24.

*******R.W. Southern, Western Society and the Church in the Middle Ages (London 1970), 136-43.