“We dare not encourage the mob very much. It goes mad too quickly…And it is better for tyrants to wrong them a hundred times than for the mob to treat the tyrant unjustly but once. If injustice is to be suffered, then it is better for subjects to suffer it from their rulers than for the rulers to suffer it from their subjects. The mob neither has any moderation nor even knows what moderation is. And every person in it has more than five tyrants hiding in him. Now it is better to suffer wrong from one tyrant, that is, from the ruler, than from unnumbered tyrants, that is, from the mob.”*

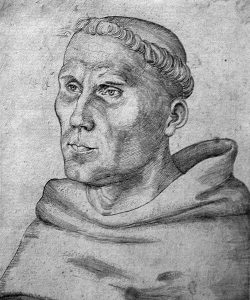

Dr. Martin Luther wrote these words in 1526 in his significant tract entitled Whether Soldiers, Too, Can Be Saved. His study of Holy Scripture and ancient history influenced his ideas stated here. In the previous section, he had explained how the Roman people overthrow many emperors. In Germany in 1524-25, large groups of peasants were ransacking castles and whole towns. They murdered many people and took over entire cities. This was an organized insurrection and some of the participants followed pseudo-prophets, who told thousands of followers to cleanse the “ungodly” from the land. The most famous of these false prophets was Thomas Müntzer. He told his followers that God would protect them from the weapons of their enemies and they would create the kingdom of God on earth.**

Dr. Luther recognized the oppression of the common man and denounced the greed of princes and trading companies (similar to modern corporations). He exhorted the princes to negotiate with the peasants and town dwellers. He excoriated the moneylenders and bankers who lent money at exorbitant interest. However, when he saw this insurrection, we usually call the Peasants’ Revolt, he called for it to be stopped with great force by the princes’ armies. The armies of the peasants numbered in the tens of thousands. They destroyed castles and attacked monasteries. They took over entire towns and often forced others to participate in their activities. Dr. Luther also made clear that any captives or those who surrendered should be treated mercifully. Eventually, the German princes used their superior armies to crush the peasants.***

Despite what I have read from many modern critics, Martin Luther did not delight in these events nor did he see the peasants’ grievances as petty. However, he knew one thing that was very important. Mobs cannot be trusted. Religious charlatans and criminals will use mobs for their nefarious purposes. Such mobs only steal and destroy. And, in the end, after the violence, most often conditions become much worse for everyone. Calls for Change often hide the real agenda of those promoting it. He concluded later in the same text:

“There is a difference between changing a government and improving it as the distance from heaven to earth. It is easy to change a government, but it is difficult to get one that is better, and the danger is that you will not. Why? Because it is not in our will or power, but only in the will and the hand of God. The mad mob, however, is not so much interested in how things can be improved, but only that things be changed. Then if things are worse, they will want something still different.”****

*Martin Luther, Whether Soldiers, Too, Can Be Saved, in Luther’s Works 46: 105-06. [Emphasis added]

**On Muntzer and his role in the Peasants’ Revolt see Carter Lindberg, The European Reformations, 2nd ed., pp. 137-150

***See Luther’s Admonition to Peace, Against the Robbing and Murdering Hordes of Peasants, and An Open Letter on the Harsh Book Against the Peasants in LW 46:17-85

****Luther, Whether Soldiers, Too, Can Be Saved, LW 46:111-112. [Emphasis added]