“There is no doubt that the monastic vow is in itself a most dangerous thing because it is without the authority and example of Scripture. Neither the early church nor the New Testament knows anything at all of the taking of this kind of vow, much less do they approve of a lifelong vow of very rare and remarkable chastity.” Martin Luther, The Judgment of Martin Luther On Monastic Vows, LW 44:252 [emphasis added]

Martin Luther wrote these words in late 1521 on the nature of monasticism. Originally, he intended this work on monastic vows (over 100 pages in the English translation) to be a guide for those now leaving the monastic life. As early as 1520, he had criticized the practice of mandated priestly celibacy and wrote that priests should be allowed to marry. In this work, Dr. Luther took on the idea of monastic vows. When someone joined a monastery or certain religious orders, he or she took vows of chastity. Compared to marriage, it was a lifelong commitment to remain celibate, not to marry, and resist carnal temptation.

Monasticism and other forms of the specialized religious life proliferated after the twelfth century to the sixteenth century. This included male and female forms of the religious life. Even many quasi-monastic groups appeared that sometimes became formal religious orders appeared. Luther had taken a vow as an Augustinian hermit to remain chaste for his life too. After 1517, he clearly began to struggle with the reasoning behind such vows. However, he did not fully reject monastic vows publicly until 1521. Although this book did not appear in print until March 1522, Luther already prepared a second edition by June 1522. Luther’s colleague, Justus Jonas, wrote a German translation of Luther’s original Latin in the same year.

This work demonstrates the logical conclusion from Luther’s theology of justification by faith in Christ and his view of the authority of Holy Scripture. He argues that monastic vows from their inception were human inventions and not commanded by God. In fact, God, according to Luther, ordained the opposite from creation as he wrote in The Estate of Marriage in 1522.

“Don’t let yourself be fooled on this score, even if you should make ten oaths, vows, covenants, and adamantine or ironclad pledges. For as you cannot solemnly promise that you will not be a man or woman (and if you should make such a promise it would be foolishness and of no avail since you cannot make yourself something other than what you are), so you cannot promise that you will not produce seed or multiply…And should you make such a promise, it too would be foolishness and of no avail, for to produce seed and to multiply is a matter of God’s ordinance [geschöpffe], not your power.” [LW 45:19]

Martin Luther did not marry until 1525. Perhaps, he did not find the right woman for him, but he wrote that he did not plan to marry before that time. Katharina von Bora, a former Cistercian nun, changed that plan. However, Luther had already come to a theological conclusion about his own (and Katharina’s) monastic vows of chastity. Vows are not based on true faith in Christ and go against the foundation of his understanding of the Bible, as he explained:

“Now it must be seen more generally that monastic vows are without faith. It has been proved, and established by irrefutable testimonies, that everything which is not of faith is sin, and that it is faith alone which effects the remission of sins and restores certainty, serenity, and freedom from sins to the conscience. Good works, however, or, to give them their proper name, the fruits of faith, do not really pertain to the remission of sins and a serene conscience, but are the fruits of a forgiveness already granted and still present, as well as a good conscience.” Martin Luther, The Judgment of Martin Luther On Monastic Vows, LW 44: 279. [emphasis added]

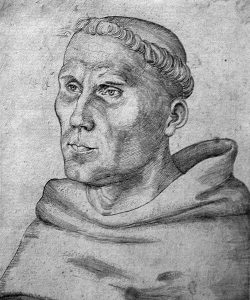

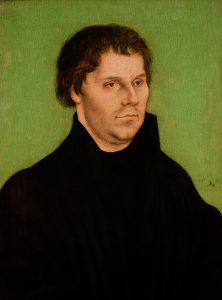

By 1526, Martin the troubled theologian and monastic hermit had become Martin the husband and father. Notice the difference in his appearance in 1525:

Doesn’t the Defense/Apology of the Augsburg Confession allow for some form of monasticism?

For example it says

– “Nor indeed do we find fault with all; for we are of the opinion that there are here and there some good men in the monasteries who judge moderately concerning human and factitious services, as some writers call them, and who do not approve of the cruelty which the hypocrites among them exercise”

And it also says

– “Secondly. Obedience, poverty, and celibacy, provided the latter is not impure, are, as exercises, adiaphora [in which we are not to look for either sin or righteousness].”

– And it is credible that in some places there are also at present good men, engaged in the ministry of the Word, who use these observances without wicked opinions [without hypocrisy and with the understanding that they do not regard their monasticism as holiness].

Doesn’t this allow being a monk provided there are no lifelong vows and you know it doesn’t make you holier than anyone else? And if it does, why are there almost no Lutheran monks around, and why are most Lutherans against it?